Global AI Governance: The Landmark Geneva Treaty of 2026

In a historic gathering in Geneva, representatives from over 120 nations have successfully negotiated the first comprehensive international treaty on AI governance. The 2026 Geneva Treaty on Artificial Intelligence sets a global foundation for the ethical development, deployment, and monitoring of autonomous systems, marking a turning point in the history of global cooperation.

The culmination of three years of intense negotiations, the Geneva Treaty represents a delicate balance between encouraging innovation and mitigating the existential risks posed by unregulated AI. At its core, the treaty establishes the 'Human-in-the-Loop' principle as a universal legal requirement for all high-stakes autonomous systems, including those used in defense, healthcare, and critical infrastructure. This means that no machine can make a life-altering decision without a verifiable human oversight mechanism. The negotiations were often fraught with tension, particularly between tech-dominant nations and those advocating for a more restrictive approach to digital sovereignty. However, the shared realization that a 'race to the bottom' on AI safety would benefit no one eventually led to this landmark consensus.

The Five Pillars of the Geneva Accord

The treaty is structured around five key pillars that define the future of global AI interaction. The first pillar is 'Transparency and Auditability.' Signatory nations agree to mandate that all foundation models above a certain compute threshold must be registered with a newly created International AI Agency (IAIA). This agency, modeled after the IAEA, will have the authority to conduct 'safety audits' and verify that models are not being trained for malicious purposes, such as chemical weapon design or sophisticated cyber-warfare. The level of transparency required was a major sticking point, but a compromise was reached allowing for third-party audits that protect commercial intellectual property while ensuring public safety.

The second pillar focuses on 'Algorithmic Accountability.' For the first time, an international legal framework defines the liability for autonomous systems that cause harm across borders. If an AI-driven financial algorithm based in one country causes a market flash-crash in another, there is now a clear pathway for restitution and investigation. This pillar also includes provisions for 'Digital Rights,' ensuring that AI systems respect the privacy and data autonomy of individuals, regardless of where the data is processed. This creates a global baseline for data protection, similar to the GDPR but on a truly international scale.

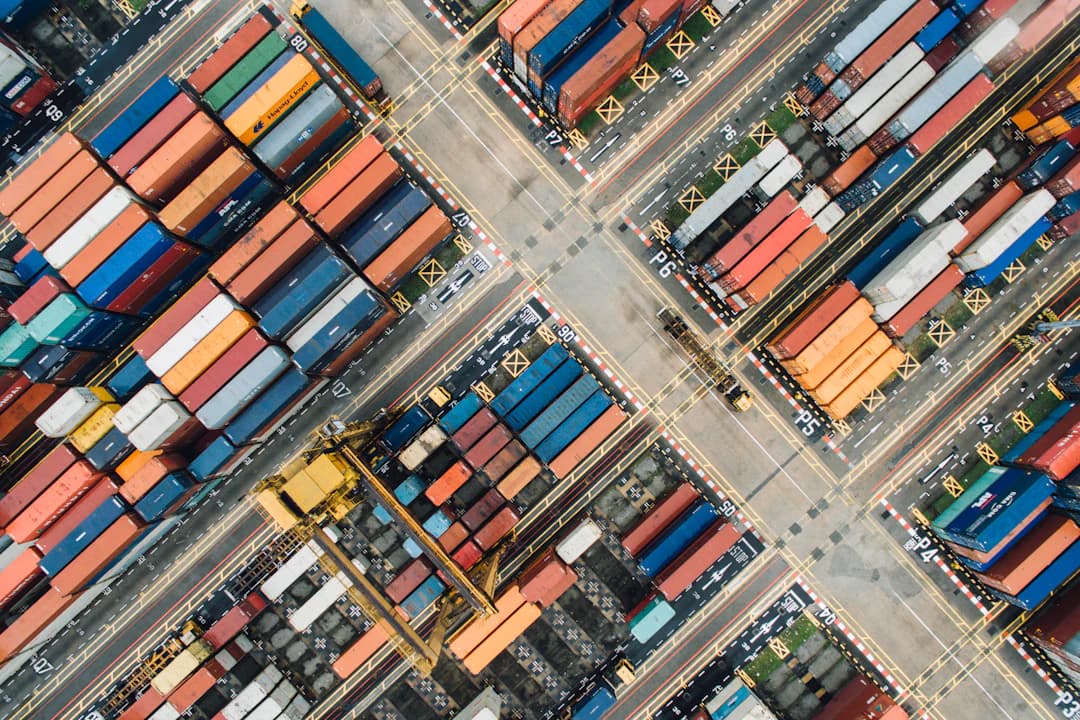

The third pillar is 'Equitable Access.' Recognizing the potential for an 'AI divide,' the treaty includes a commitment from developed nations to share 'safety-critical' AI technologies and compute resources with the Global South. This is not just a philanthropic gesture; it is a recognition that global stability depends on the inclusive growth of AI capabilities. The 'AI For All' fund, established by the treaty, will provide grants for research into AI applications that address climate change, pandemic prevention, and agricultural optimization in developing regions. This pillar was championed by a coalition of nations in Africa and Southeast Asia, who argued that without such protections, AI would simply become a new tool for neo-colonialism.

The fourth pillar addresses 'Autonomous Defense Systems.' While a total ban on lethal autonomous weapons (LAWS) was not achieved, the treaty imposes strict limitations on their development and deployment. It prohibits the use of AI in nuclear command and control systems and mandates that all autonomous weapons must comply with the Geneva Conventions' principles of distinction and proportionality. This 'Red Line' agreement is seen as the most significant arms control measure of the 21st century. The negotiations in this area were the most difficult, with several major powers initially resistant to any limits on their military capabilities. However, the pressure from the global scientific community and civil society proved decisive.

The fifth and final pillar is 'Sustainability and Environmental Impact.' AI training and inference are energy-intensive processes, and the treaty sets mandatory targets for the carbon footprint of large-scale AI operations. Signatories must ensure that their major AI data centers are powered by renewable energy by 2030 and must participate in a global carbon-offset program for AI-related emissions. This integrates AI governance with the Paris Agreement goals, acknowledging that the digital revolution cannot come at the expense of the planet's health.

The Role of the International AI Agency (IAIA)

The IAIA, headquartered in Vienna, will serve as the technical heart of the treaty. It will be staffed by a diverse array of experts, from computer scientists and ethicists to lawyers and career diplomats. Its primary mission is to provide independent verification of treaty compliance and to facilitate international cooperation on AI safety research. The agency will also host a global 'AI Safety Clearinghouse,' where nations can report vulnerabilities and 'near-miss' incidents in autonomous systems. This collective intelligence model is designed to prevent systemic failures before they occur. The funding for the IAIA will come from a small levy on large-scale commercial AI compute, ensuring that the industry itself contributes to the governance that makes its existence possible.

The Geneva Treaty is not an end, but a beginning. It is the roadmap for a future where technology serves humanity, and not the other way around.

Criticisms and Challenges Ahead

Despite the optimism, the treaty has its critics. Some technology industry leaders argue that the registry and audit requirements will stifle innovation and favor established players who can afford the compliance costs. On the other end of the spectrum, some activists argue that the treaty does not go far enough, particularly regarding the ban on autonomous weapons. There are also concerns about enforcement, as the IAIA lacks the hard power to punish non-compliant nations directly. Instead, it relies on 'reputational costs' and potential sanctions from other treaty members. The success of the Geneva Treaty will ultimately depend on the political will of the major powers to uphold its principles, even when they conflict with short-term national interests.

Moreover, the rapid pace of AI development means that the treaty will need to be a 'living document.' Provisions that seem robust today may be obsolete in eighteen months. To address this, the treaty includes a 'Dynamic Review Mechanism' that requires a full review of all technical standards every two years. This agility is unprecedented in international law but is considered essential for governing a technology that evolves at exponential speeds. The first review is already scheduled for 2028, and delegates are already anticipating the challenges that advances in quantum-AI integration will bring.

A New Era of Digital Diplomacy

The Geneva Treaty of 2026 marks the birth of a new field: Digital Diplomacy. It is no longer enough for diplomats to understand geography and history; they must now understand neural networks and compute complexity. The success of these negotiations has set a precedent for how other global digital challenges, such as space debris and bio-informatic security, might be handled. It signals a move away from the 'wild west' of the early internet era toward a more structured and responsible global digital order. As the world begins the difficult work of implementing the treaty, the spirit of Geneva—collaborative, pragmatic, and forward-looking—offers a glimmer of hope in a world often defined by division.

To further expand on the implications, we must look at the specific impacts on various sectors. In the financial world, the 'Algorithmic Accountability' pillar is expected to lead to a more stable but perhaps less efficient market in the short term, as firms adjust to new risk-management mandates. In healthcare, the 'Human-in-the-Loop' requirement is being hailed as a win for patient safety, ensuring that diagnostic AI remains a tool for doctors rather than a replacement. The education sector is also seeing shifts, with the treaty's emphasis on equitable access prompting new international partnerships for AI-enhanced learning. These ripple effects demonstrate that the Geneva Treaty is not just a political document; it is a foundational shift in how our global society functions. The coming decade will be the true test of this vision.

Finally, the impact on individual privacy cannot be overstated. The treaty's focus on data autonomy and cross-border liability gives individuals a level of protection never before seen on a global scale. It creates a framework where personal data is treated as an extension of the person, requiring explicit and informed consent for its use in AI training. This 'Digital Habeas Corpus' is perhaps the most revolutionary aspect of the treaty for the average citizen. As we move into the late 2020s, the Geneva Treaty of 2026 will likely be remembered as the moment when humanity collectively decided to take the reins of its technological destiny. The path ahead is long and uncertain, but for the first time, we have a map.

Related Post

The 2026 Midterm Shift: A Deep Dive into the Battle for the House

The UN Leadership Transition: Predicting the Next Secretary-General

Global Summit Addresses Rising Inflation Concerns

New Trade Policy Shifts Economic Alliances in Asia

RECENT POST

- »Artemis II: Humanity's Return to Lunar Orbit in February 2026

- »FIFA World Cup 2026: The Global Stage Set for North America

- »The 2026 Midterm Shift: A Deep Dive into the Battle for the House

- »The IPO Renaissance: Why 2026 is the Year of the Megadeal

- »AI Meta-Agents: The Next Evolution of Multi-Agent Systems in 2026